The Centre of Advanced Study Department of History has recently reprinted the Persian text of Muntakhab ut Tawārīkh which had earlier been published during late 19th Century from Calcutta. Since more than a century it is not available to the public being out of print since long. No publisher was ready to take up it’s reprint as, according to them, it had no “market”! It wouldn’t sell! Thus we took up the challenge. All the three volumes have been printed afresh in collaboration with the Publications Division, AMU. I am really thankful to the former Director Sir Syed Academy and Incharge Publications, Professor Tariq Ahmad, and his Deputy, Dr Husain Haider for facilitating the publication of all the three volumes. I am also thankful to the present Director & Incharge Maulana Ali Muhammad Naqavi.

Thanks are also due to Professor Emeritus Irfan Habib for agreeing to write a fairly detailed and thoroughly researched Introduction to the text. It adds to the value of this edition of the Muntakhab ut Tawārīkh.

Here I present to you my analysis of Badauni and his history.

***

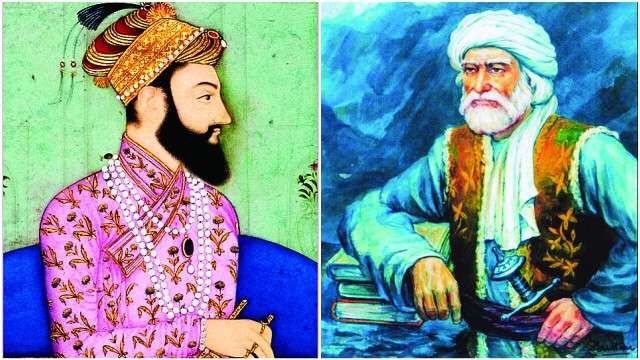

Mulla Abdul Qadir Badauni’s work is a history of the Muslim rule in India from the Ghorian invasion down to the end of Akbar’s reign written from a religious bias. Thus in this work, the history of Akbar’s reign is written from the orthodox Sunni point of view. Naturally it tends to become a critic of Akbar’s policies based on principles of Sulh i kul. This kind of version with such bias is important and useful in our study of the political history of the reign as it serves as a balancing narrative to the account furnished by Abul Fazl in the Akbarnama, which as we know, is an account written with a bias to justify Akbar’s policies that were framed in the light of the policy of Sulh i kul. It is also written from the point of view of projecting Akbar as an insan-i kamil whose mission was to establish peace amongst people, unity of purpose in the state, and extend state patronage to a large group of people.

This view forwarded by Abul Fazl stands corrected by the sharp criticism which Badauni offers for the policies of Akbar.

We know from the notings which Badauni had made in volume III that he completed the book in 1004 AH / 1596. But the work could come out in the public only around 1616. For about twenty years after its completion, the book was not released for circulation. It is understandable why Badauni was hesitant to have it circulated during his lifetime. He knew if the book went into circulation, it would attract hostility of the Mughal authorities. We may assume, it was not in circulation till 1614, at least on the basis of the fact that in the list of different sources available, say that of Abdul Baqi Nahawandi (Ma’asir-i Rahimi), the name of Muntakhab ut Tawarikh is missing – a significant negative piece of evidence pointing towards the fact that till 1614-16 this was not in circulation. Subsequently, when the book did come in circulation, Jahangir made enquiries about the hostile remarks against his father.

Thus it was not for the perusal of the King. His style as a result, is not constrained by any fear of punishment or reprisal.

So far as the structure of the book is concerned, it is divided into three volumes. The first volume deals with the history of the Muslim rule in North India from the Ghorian invasion down to the end of Humayun’s reign, i.e., 1556.

An internal examination of the book reveals that Badauni derived information from two sources: the Tarikh-i Mubarakshahi (Yahya bin Ahmad Sirhindi) and the Tabaqat-i Akbar. For the later Sur period, Badauni bases on personal information and partly on information available to him through other sources.

Badauni’s account of the Sur Empire, for the period between 1553-56 is very significant and original. This is the only detailed account we have which gives the political developments under Adil Shah Sur and others who put forward their claims to the Sur throne.

The second volume of the Muntakhab deals with the history of Akbar’s reign down to the 40th RY (1595). The last event which Badauni records in this volume is Faizi’s death which took place in 1595. He adds a cruel note to this event.

The third volume comprises a large number of biographies of the mashaikh, ulema, physicians and poets: he gives biographic details of 38 important mashaikh, 49 leading ulema, 15 reknowned physicians and 167 well known poets of his own time. For this he borrowed much material from the Tazkiras of the poets that were compiled by Alauddaulah Qazwini as part of his Nafais ul Ma’asir.

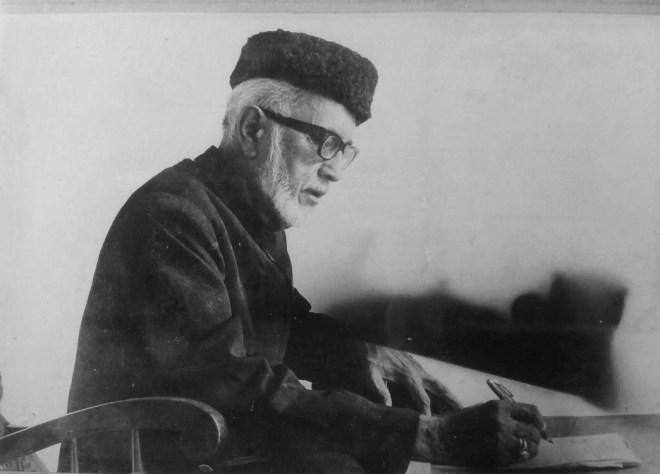

Badauni, as against what his name suggests, did not hail from Badaun: he hailed from Kota Bhim in Rajasthan, which at that time was included in the Kachhwaha principality of Amber. He was born in 1541. His father, Muluk Shah, shifted to Agra in early 1550’s and stayed there down to 1561. It was after 1561 that the family shifted to Badaun and settled there.

Abdul Qadir Badauni received his early education at Agra under Shaikh Mubarak, who was at that time, known for his learnings towards Mahdavism. For some time, he also studied with Miya Hatim Sambhali, an orthodox teacher of early ‘60’s.

Badauni had become accomplished in a number of arts and sciences. In a letter written by Faizi to Akbar regarding Badauni, it is stated that he was proficient in history, astronomy, art of qir’at, music – especially Indian music and was a player of bīn. He also had expertise in chess. So Badauni was not only an ālim but otherwise also he was an accomplished person. Badauni himself does not refer to his proficiency in chess and music while writing his book.

So far as the history of his service career is concerned, he took up service under Husain Khan Tukriya in 1564, in which he continued down to 1574. In 1574 Badauni entered the Imperial service as the imam of the army for one of the days of the week. He was appointed to this minor position simultaneously with the appointment of Abul Fazl who took up the same position.

In fact Badauni laments that while Abul Fazl used flattery and readiness to agree with superiors to rise to the position of a high noble – a position which Badauni did not, as he did not worry about worldly gains. His bitterness is obvious in this statement. It is obvious even in vol. III when he writes about Abul Fazl and Faizi.

So far as the significance of the Muntakhab ut Tawarikh as a source is concerned, the problem has been discussed in at least three modern writings:

a. Elliot’s Introduction on Badauni with his translation.

b. Prof Muhammad Mujib’s paper in the edited work of Prof Muhibbul Hasan published from Jamia.

c. Discussion of Badauni’s approach to interpret history of Akbar’s reign by S Athar Abbas Rizvi in two of his works, viz., Muslim Revivalist Movements and the Intellectual Life under Akbar.

Still, here one would like to highlight some aspects of Badauni’s approach in interpreting Akbar’s reign missed in the above mentioned works.

A serious contradiction seems to have run through the entire narrative of Badauni in volume II & III of his work. This contradiction is that he gives conflicting assessments of Akbar as well as his policies and the role played by persons close to Akbar. Such contradictions are found within different parts of volume II itself as well.

We find that while at most places in volume III – and in certain places in volume II – Badauni refers to Akbar with great respect. He calls him khalifat uz zamān. But then on the other hand, in the major part of volume II, from 1575 onwards, he seems to be so annoyed with Akbar that he does not refer to him with name. He is found levelling charges in this part and he seems to have forgotten his respectful attitude depicted elsewhere. He charges Akbar of prohibiting namaz of the Muslims – a charge which on face appears to be unsubstantiated. He also accuses Akbar of forcing ulema to shave their beards; of enslaving ulema and mashaikh in large numbers nd exchanging them with horses and donkeys in the markets of Qandahar and Bhakkar. He also alleges that Akbar tried to impose ban on the learning of Arabic language. In general, in this part, he shows his disrespectful attitude towards Akbar. So one can very well see that the author had described the same person as a khalifat uz Zaman and, as a heretic.

Then there are other specific cases of contradiction: for example, the manner in which he assesses the role of Shaikh Salim Chishti in volume II and then in volume III. In volume III, when he gives a biographical sketch of the Chishti saint, Badauni gives a positive assessment of Salim Chishti’s character from the Islamic point of view.

But then in volume II, Badauni says:

And such was the disposition of that paragon of excellence, His Grace, the Shaikh, that he allowed the emperor entry to all his most private apartments, and however much his sons and nephews kept saying ‘Our wives are becoming estranged from us’, the Shaikh would answer, ‘There is no dearth of women in this world, since I have made you Amirs, seek other wives, what does it matter?’

(verse) Either make no friendship with an elephant driver,

Or make a house fit for an elephant.

The assessment of Shaikh Mubarak and his beliefs is given in volume III and II.

In volume II Badauni says that at one occasion Shaikh Mubarak told Birbal:

‘Just as there are interpolations in your Holy Books, so there are in ours. Hence it is impossible to trust either’.

Could this be said even by a ‘bad’ Muslim?

But then in volume III, Badauni contrarily noted:

He (Sh. Mubarak) was one of the great sages of the age and was distinguished amongst men of his time for his piety, devotion and trust in God. In early life he observed many austerities and strove much in the way of holiness and was zealous in enforcing commands and prohibitions of the Holy Law that if any body present was wearing a gold ring, or silk clothing, or red hose or red or yellow garments, he at once made him remove them, and if anyone appeared with long breeches, descending below the hell, he immediately had them torn to proper length.

Badauni accuses him of joining heretics, but does not charge him of being an apostate. Thus he says:

…and the pity is that his love of the world with its pomps, concealed under the garment of hiding poverty, left no room for the love of faith of Islam. [III, 120]

Similar contradictions are there about Shaikh Faizi: In volume III he has abuses reserved for him. At one place he acknowledges that favours were done to him by Faizi by giving him letters favouring him and introducing him. But then at other places, he makes fantastic accusations against Faizi: says Faizi’s poetry was not appreciated by contemporaries and his books were not considered as worthy by literary people.

Lastly, let us quote one observation about Faizi which he made while giving the biography of Shaikh Abdul Haq Muhadis Dehlavi and his great affection for Faizi:

Glory be to God! Shaikh Faizi has passed away and become a by-word; and as far these, the mention of whom is still among us for a few days, or rather for a few hours, who are they that we waste time in addressing them where preparation is even now being made for our departure hence? All that remains to them is the wind of speech. How long shall we waste our time in measuring it?

From these examples, it becomes evident that

(1) Badauni had more unbalanced views and assessments of contemporaries when writing volume II.

(2) The nature of criticism in volume III is sometimes qualitatively different from the kind of accusations in volume II.

(3) In the volume II the views are more balanced.

This goes to suggest that most probably Badauni compiled volume III at a time when he had not yet developed that kind of imbalanced view of the situation reflected in volume II.

At the end of volume III, treated by us as the final volume, Badauni says, it was compled in 1595. In the light of inferences drawn from the internal evidence, we would be justified in making the bold suggestion that the volume treated as volume II was compiled by Badauni after 1595 (that is, after volume III).

It is significant to note that at the end of volume I, Badauni actually has given an epilogue in which he states clearly that it was his plan to write the next volume comprising the biographies of contemporary poets:

Should this inconsistent and transitory life give (the author) a few days respite, and should the days in opposition to the usual habit afford assistance and should fate give its help, he (i.e., Badauni, the author) will make mention of poets of former times and of the contemporary poets of Hindustan, especially of those whom he had seen or heard or appreciated in his own lifetime together with extracts from their poems included in the tazkiras.

What, through these internal evidences we are trying to suggest and establish is that most probably, the volume which is now considered as volume II, containing the history of Akbar’s reign, was written sometime after the completion of History of Muslim Rule from earliest time in Humayun’s reign, and also after the penning of the biographical sketches of the contemporaries in volume III.

Perhaps Badauni compiled this second volume at a time when his assessment of the situation had undergone a considerable shift since the time he had completed the other two volumes.

This is borne out by the contradictory assessments that he gives of Akbar’s policies, Akbar’s character and the role of contemporaries in the two places ~ the second volume and the first and third volumes. It seems that by the time he started finalising vol II, his views had become rather extremist. By that he had come to the conclusion that the position of Islam in India had become untenable due to many factors including Akbar’s policy, and he was trying to put it straight by apportioning the blame of the catastrophe.

But then, in vol II as well, we find that in the first portion, he is not having an alarmist position which he has in the second half. In the portion relating to the post 1574-75 period, his views are most extremist.

In the first part of Vol II, he is calling Akbar as Khalifat al zaman, while in the second half, he charges him of heresy. This gives an impression that the account presented in Vol II is based on some journal which he maintained reflecting his changing assessment of the situation when he is becoming extremely critical.

His unbalanced attitude and state of mind is reflected in vol III also when he tries to revise and appends additional paras in individual biographies. To give an example: in the biography of Shaikh Mubarak, when he is beginning, he is praising and is not critical, as in the last paragraph which seems to have been added afterwards when his views had radically changed.

Then he also gives a number of chronograms giving dates of important events.

Thus in 1562, Pir Muhammad Khan Sherwani died during a campaign in Malwa by drowing in Narbada. Badauni writes:

“ba rāh-i āb ba jahannum raft”

When Muzaffar Kahn Turbati (a Khurasani) was appointed as the wakil in 971 AH, the fact is given by Badauni by the chronogram “zālim” (971) [oppressor]. Similarly on the death of Shaikh Gadai Kanboh, the sadr: murda khūk-i kalān [You are dead you great hog!]

When in 971 Ah, a certain Qazi of Baran was given capital punishment, Badauni found the chronogram of this event as “qāzi lāl”. And when Shaikh Ibrahim Chishti of Fathpur Sikri died in 999 AH, Badauni wrote that “since he was noted and notorious for avarice and vice, and was accursed”, his chronogram found was ‘Shaikh laīm’ [ “Base of disposition” or “Vile Shaikh”].

On the death of Urfi Shirazi, the famous poet the same year, he uses the term dushman-i Khuda.

Similarly on the execution of Ali Quli Khan Uzbek Khan-i Zaman and Bahadur Khan, after their rebellion in 1567 (974 AH), one of the chronograms found was “qatl-i du namak harām be dīn”

Incidentally all these persons were Shias.

One can see that all these chronograms have a common quality of being cruel, pungent and in bad taste. Badauni doesn’t say that they were compiled by him but it is obvious that they are of him only, having the dame pungent effect as in his prose. Probably he composed them when he was preparing the journal which ultimately was used to draft vol II.

An additional indication of this journal being maintained by Badauni is supported by other evidences as well.

He is becoming more and more hysterical in denouncing Akbar. If he would have been such in the earlier period as well, it would have reflected in the earlier period as well.

It is true that Badauni was very orthodox, but what he had to say regarding the role played by the Mahdavi leaders during Islam Khan’s reign, shows that he not only had very great respect and admiration for them, but he also shared the harsh cricism which Mahdavi leaders were making of the orthodox Ulema. So far as his admiration for Mahdavi saints is concerned, it is borne out by the chronogram he gives of Shaikh Alai’s death in 978 AH: zikr Allah.

Regarding Shaikh Alai, he says:

“Shaikh Alai who was the most orthodox of the sons of Shaikh Hasan, the tablet of whose forehead was from early boyhood distinguished by marks of nobility and uprightness and evidences of a youth to be spent in the worship of God and in following the ordinances of the Prophet of God.”

Badauni also praises Shaikh Alai’s piety, his indifference to worldliness and goes on to reproduce with much gusto and glee the denunciation of Makhdum ul Mulk Abdullah Sultanpuri by Sh. Alai at Islam Shah’s court. He puts the following words in Sh. Alai’s mouth in his vol I:

“You are one of the learned men of the world, a thief of religion, and you are engaged in so many illegal practices that you have put yourself outside the pale of equity so that even to this time the sound of pipe (nafiri: music) and tambur may be plainly heard issueing from your house, and in accordance with the true traditions of the Prophet, Upon Whom Be Peace and Blessing, a fly which settles upon filth is by degrees better than learned men who have made kings and emperors the object of their ambition and go from door to door.

Verse: Learning which exists for the sake of palace & garden

Is like a lamp to the loving thief.

This point is important from two angles: Badauni is not that sort of an orthodox as is generally conceived. He is espousing the cause of an Islamic sect regarded as heretic by majority ulema. This also helps us to see as to what was the source which influenced him in forming a very hotile and critical view of the contemporary ulema reflected in vol II where he says for the decline of Islam during his time, hypocrisy of orthodox ulema was as much responsible as the heretical views of Akbar and his advisors. In vol III he denounces ulema for the persecution of Mahdavis and writes about all types of discrepancies of the ulema.

It is much propagated that Badauni was a very intolerant person. At the same time, it is significant that when it comes to relating the role of Kachhwahas – Bhar Mal, Man Singh etc, he never uses that kind of hostile language which he employs for other nobles. He never uses an obscene language towards them. He also goes out of his way in condoning many of Akbar’s actions giving concessions to non-Muslims, especially those in which these actions and concessions are meted out to the Kachhwahas.

In 1576, when Man Singh was appointed as the commander of the expedition which was proceeding against Rana Pratap, Badauni decided to join it to fulfil obligations of jihad. Before he set out for Ajmer, one friend raised a question: ‘If you are really going from a purely religious angle, then how can you justify fighting under the command of a Hindu?’ Badauni was puzzled. Then he said that he had been appointed by a Muslim king, so it would remain a jihad! Shoot whatever side you want, all are non-Muslims.

Regarding Salim’s marriage to the daughter of Bhagwandas, he reports that the marriage ceremony was solemnised twice, first through Muslim, and then the Hindu rites: but he never makes any adverse comment, which is significant. Reason lies in the fact that Badauni had great respect for both Bhagwandas and Man Singh due to the fact that they refused to compromise their religion and accept the new creed that Akbar was trying to project. This is borne out by the approving manner in which he quotes two conversations, one between Akbar and Bhagwandas, and the other between Akbar and Man Singh.

When Akbar proposed to Bhagwandas to enrol as a member of Tauhid-i Ilahi, Badauni reports that Bhagwandas retorted:

‘I would willingly believe that Hindus and Muslims each have a bad religion. But only tell us what this new sect is and what opinion they (its members) hold, so that I may believe!’

Badauni then goes on to add: ‘His Majesty reflected a little and ceased to urge the raja!’

According to Badauni, the real culprits were those who sided with Akbar’s new religion based on principles of Sulh-i Kul, who were compromising their religion.

From this it is clear, his grouse was against those who thus compromised their faith and became a threat for the existence of Islam in India. He appreciated any one who was not impressed by the principles of the new belief.